Religion and Belief among immigrants to Canada

Immigrants to Canada are significantly more religious and more open to public religious expression than non-immigrant Canadians.

Introduction

Canada prides itself on being a country that welcomes immigrants. When asked what makes their country distinctive, many Canadians point to the diversity that comes from people from all over the world making “the true north, strong and free” their new home. Moreover, as birth rates in the North Atlantic world decline, immigrants are making up an increasing share of Canada’s population. In 2021, nearly one in four Canadians (23 percent) were born in another country—the highest proportion of the population since Confederation and greater than any other G7 country—and Canada plans to welcome 500,000 immigrants annually by 2025.1

When these individuals and families come to Canada, they bring with them their cultures, languages, traditions, and practices, all of which play a part in making Canada the country that we know today. One of the important but often underappreciated ways that immigrants contribute to the diversity of Canadian society is through their religious and spiritual lives: their beliefs, worship and spiritual practices, and participation in communities of faith. In this brief, we use survey data to look at faith and spirituality among immigrants to Canada, focusing on two main questions:

- Do the religious beliefs and practices of immigrants differ from those born in Canada, and if so, how?

- How do immigrants view the role of religion in Canadian public life, and how do their views compare to the views of those born in Canada?

It is important to note that the focus of this brief is not immigrants’ religious affiliation, that is, whether the person identifies as a Christian, a Muslim, or some other faith.2 We are interested instead in the extent to which people’s faith commitment shapes their everyday lives, both personally and publicly. Faith and religiosity are, of course, hard to measure. In this brief, the lens through which we observe Canadians’ faith lives is the Spectrum of Spirituality, a composite index developed by Cardus and the Angus Reid Institute to observe religion and spirituality along a continuum of commitment (see sidebar).

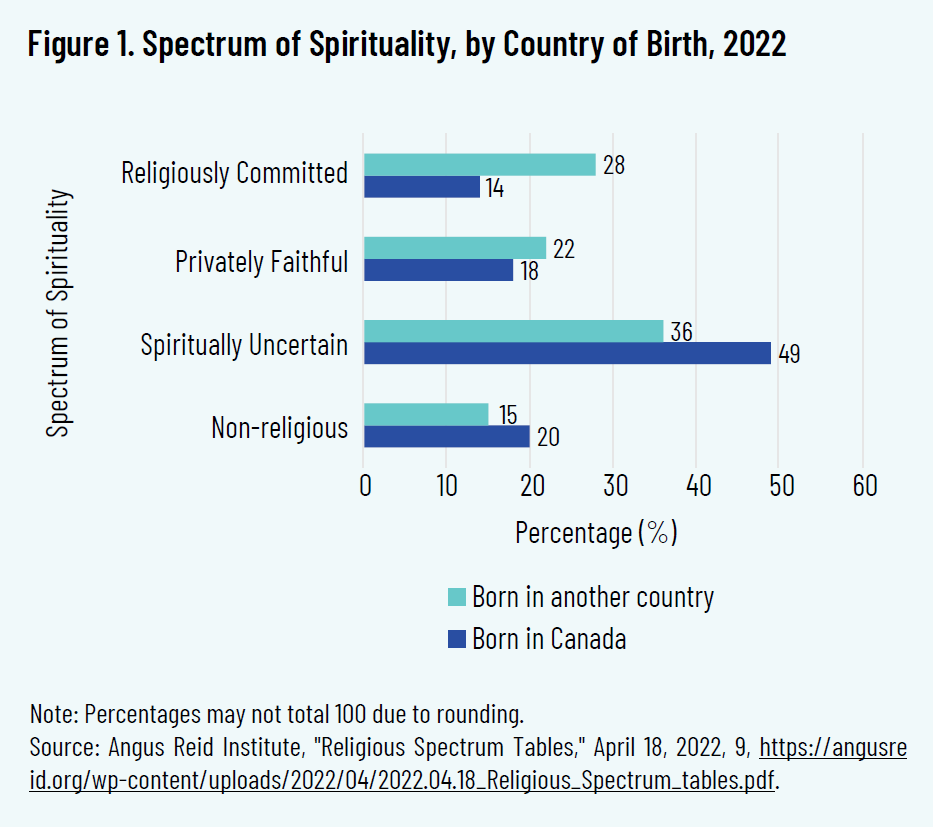

Survey data from 2022 suggest that immigrants’ beliefs and practices make them more likely than people born in Canada to fall on the more committed end of the Spectrum and to see a larger role for religious expression in public life than those born in Canada.

Those born in another country are twice as likely as those born in Canada to be Religiously Committed. Nearly seven in ten people born in Canada can be categorized as Spiritually Uncertain or Non-religious, compared to just half of immigrants to Canada (figure 1).

The Spectrum of Spirituality Index

The Spectrum of Spirituality Index was developed by Cardus and the Angus Reid Institute in order to provide greater nuance about Canadians’ religious identities and their spiritual lives.

Consider two hypothetical Canadians who select “Protestant” when responding to a survey question asking them what their religion is. One respondent selects Protestant because they were baptized in a church but otherwise have no involvement with the faith. The other respondent selects Protestant because they follow their church’s teachings and practices on a weekly basis. The Spectrum of Spirituality seeks to reveal these types of distinctions within Canadians’ religious self-understanding and to explore the role that spirituality and religious beliefs and practices play in Canadians’ lives.

Canadians are asked these questions about their beliefs and practices:

- whether they believe in God or a higher power;

- whether they believe in life after death;

- how important they think it is for a parent to teach their children about religious beliefs;

- how often, if at all, the person feels they experience God’s presence;

- how often, if at all, the person prays to God or a higher power;

- how often, if at all, the person reads the Bible, Qu’ran, or other sacred text; and

- how often, if at all, the person attends religious services (other than weddings or funerals).3

Based on their answers, respondents are placed into one of four categories along a continuum, named Non-religious, Spiritually Uncertain, Privately Faithful, and Religiously Committed. As of the spring 2022, the Spectrum enables reporting not only that 18 percent of Canadians identify as Protestant, for example, but that 10 percent of these Protestant Canadians are Non-religious, 56 percent are Spiritually Uncertain, 25 percent are Privately Faithful, and 9 percent are Religiously Committed.

The Spectrum was designed to incorporate a wide continuum of faith and spirituality across Canada’s main religious traditions. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that some of the index’s indicators may be less applicable measures of religious commitment for religions that place less emphasis on (for example) institutional religious practices or sacred texts.4

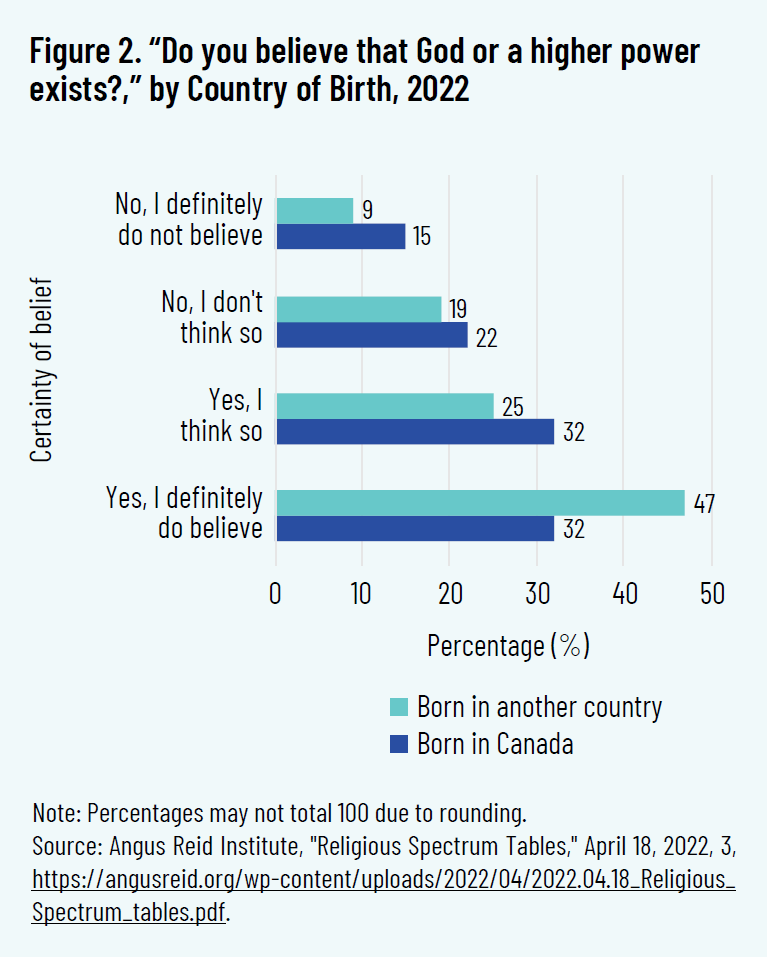

Belief in God or a Higher Power

When asked whether they believe in God or a higher power, most Canadians answer in the affirmative (though some with more certainty than others). However, this belief is stronger among immigrants than among those born in Canada: 72 percent of Canadian immigrants say they believe in God, of whom nearly two-thirds say that they are certain of their belief. In comparison, 64 percent of non-immigrant Canadians report believing in God or a higher power, split evenly between those who say they definitely do believe and those who say they think they do believe. Only 9 percent of immigrants say that they definitely do not believe, while 15 percent of those born in Canada say this (figure 2).

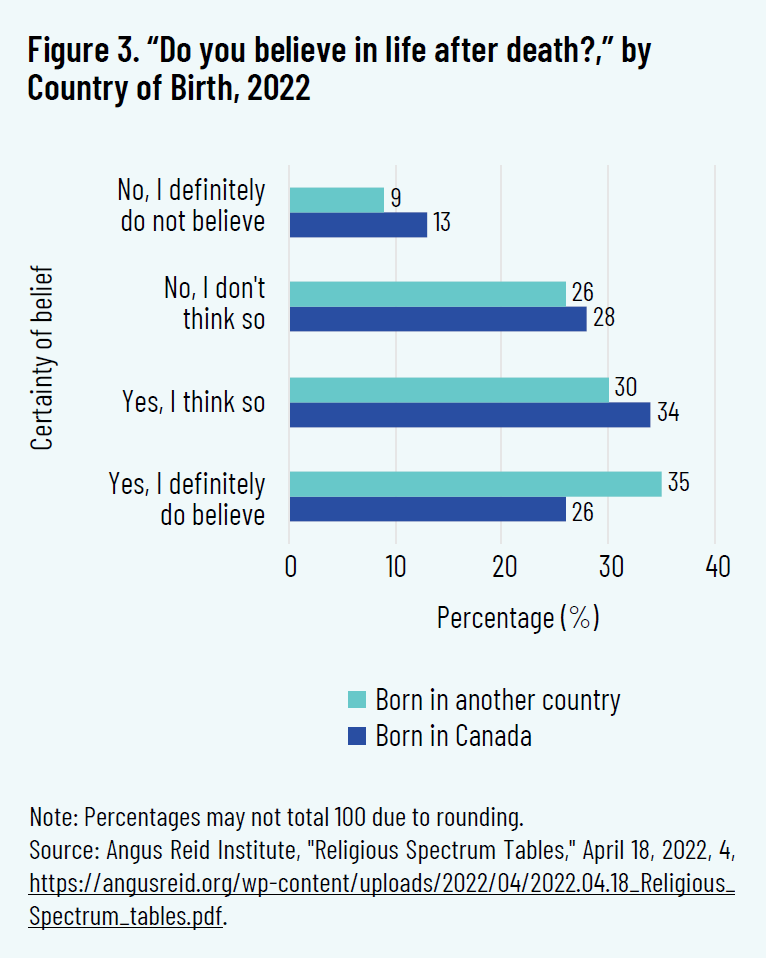

Belief in Life After Death

Immigrants are also more likely to say they believe in life after death, though by a narrower margin. Around one third of immigrants (35 percent) say they definitely believe, compared to one quarter of those born in Canada (26 percent) (figure 3).

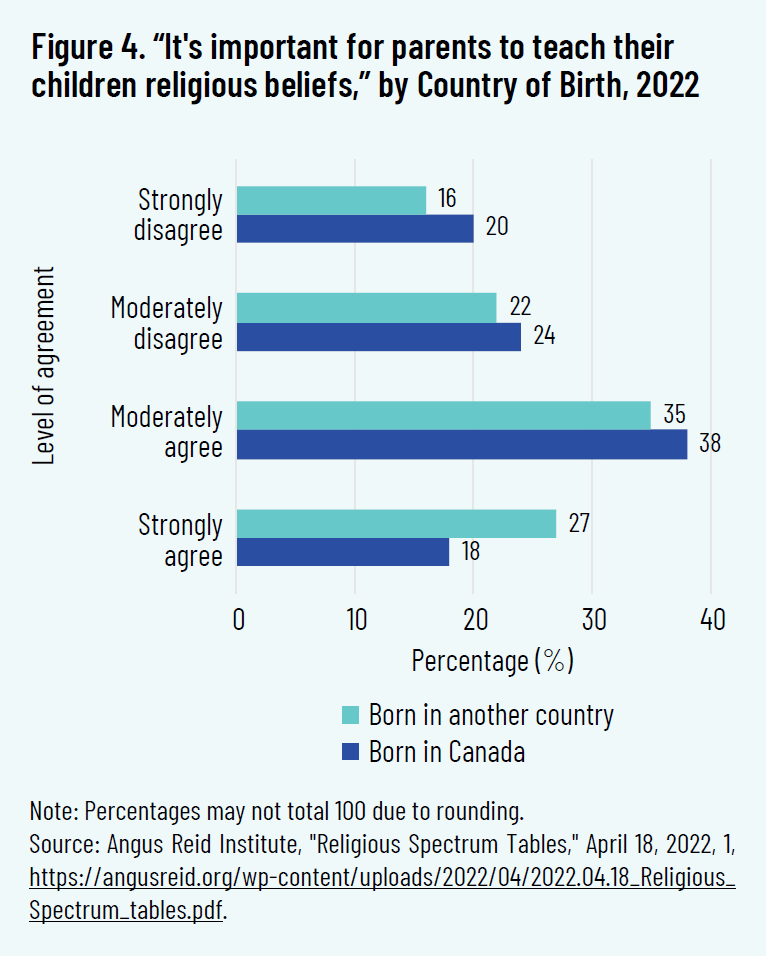

Teaching Children Religious Beliefs

Most Canadians agree that it is important for parents to teach their children religious beliefs, but immigrants are somewhat more likely to hold this view than those born in Canada. Just over one quarter of immigrants (27 percent) strongly agree that parents should teach religious beliefs to their children, while less than one in five Canadian-born respondents (18 percent) share this strong agreement (figure 4).

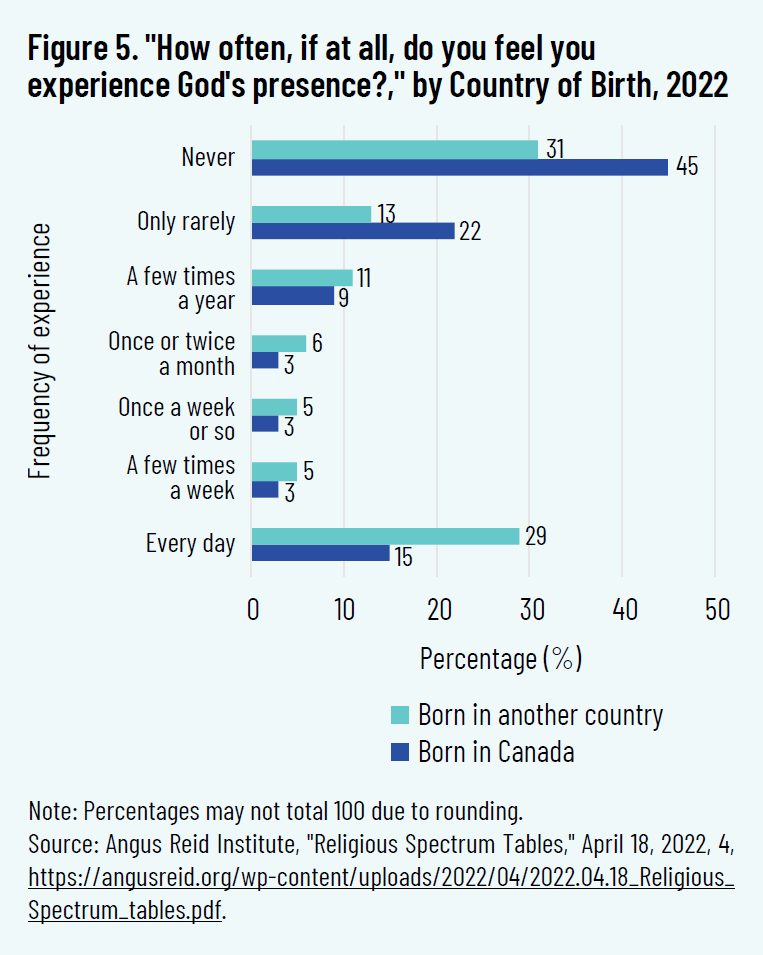

Experiencing God’s Presence

When asked how often they felt they experienced God’s presence, immigrants report having this experience more often than their Canadian-born counterparts. Immigrants are around twice as likely to say they experience God’s presence every day (29 percent, compared to 15 percent), while those born in Canada are about one and a half times as likely to say they never experience this (45 percent, compared to 31 percent). Almost half of immigrants (45 percent) report experiencing God’s presence at least once a month, compared to just under a quarter of those born in Canada (24 percent) (figure 5).

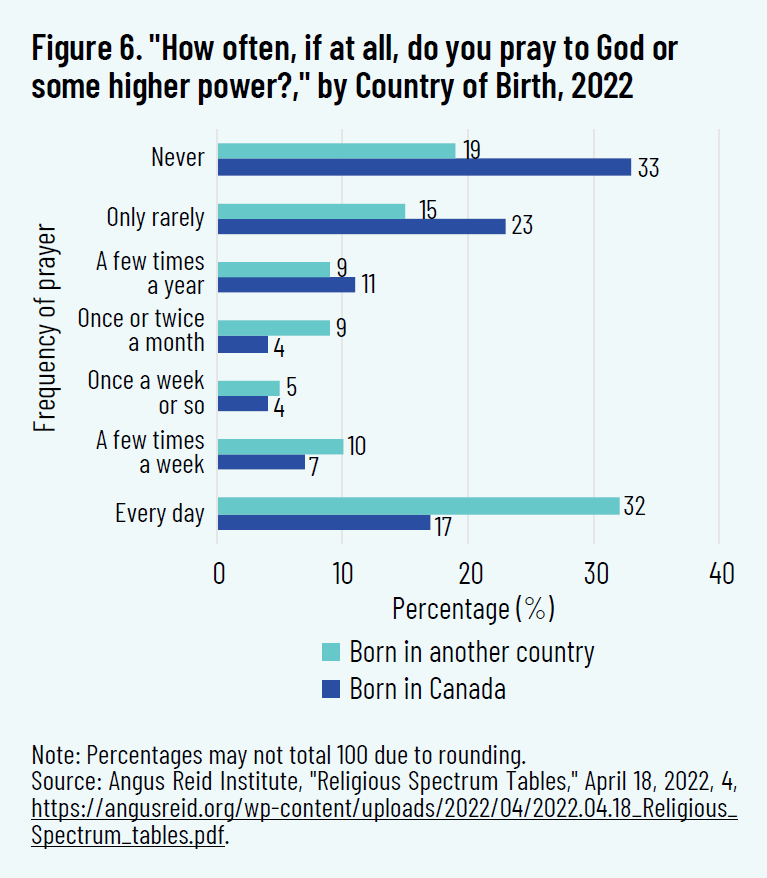

Prayer

Immigrants report praying more often than their Canadian-born counterparts. When asked how often they pray to God or a higher power, more than half of immigrants (56 percent) say that they do so at least once or twice a month, compared to one-third of those born in Canada (32 percent). Immigrants are more likely than non-immigrants to say that they pray every day. In contrast, non-immigrants are more likely, by almost the same margin, to say that they never pray (figure 6).

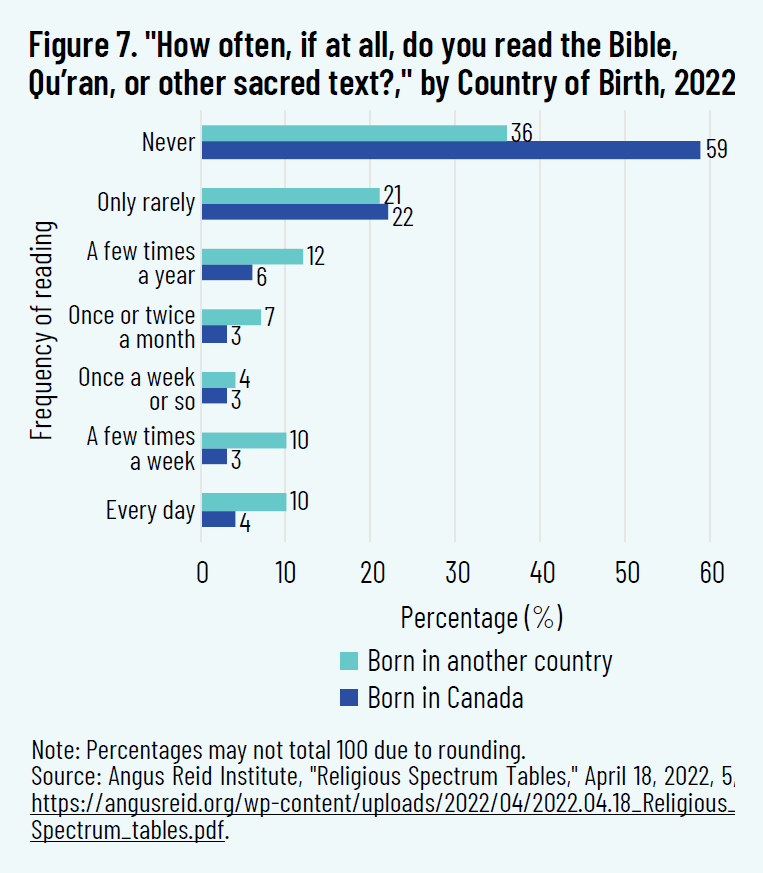

Reading a Sacred Text

Compared to those born in Canada, immigrants are more likely to say that reading a sacred text, such as the Bible or Qu’ran, is a regular part of their lives. One in five immigrants (20 percent) report reading a sacred text at least a few times a week—nearly three times the proportion of those born in Canada say the same (7 percent). Almost six in ten Canadian-born respondents (59 percent) say they never read a sacred text; only around a third of immigrants (36 percent) say this (figure 7).

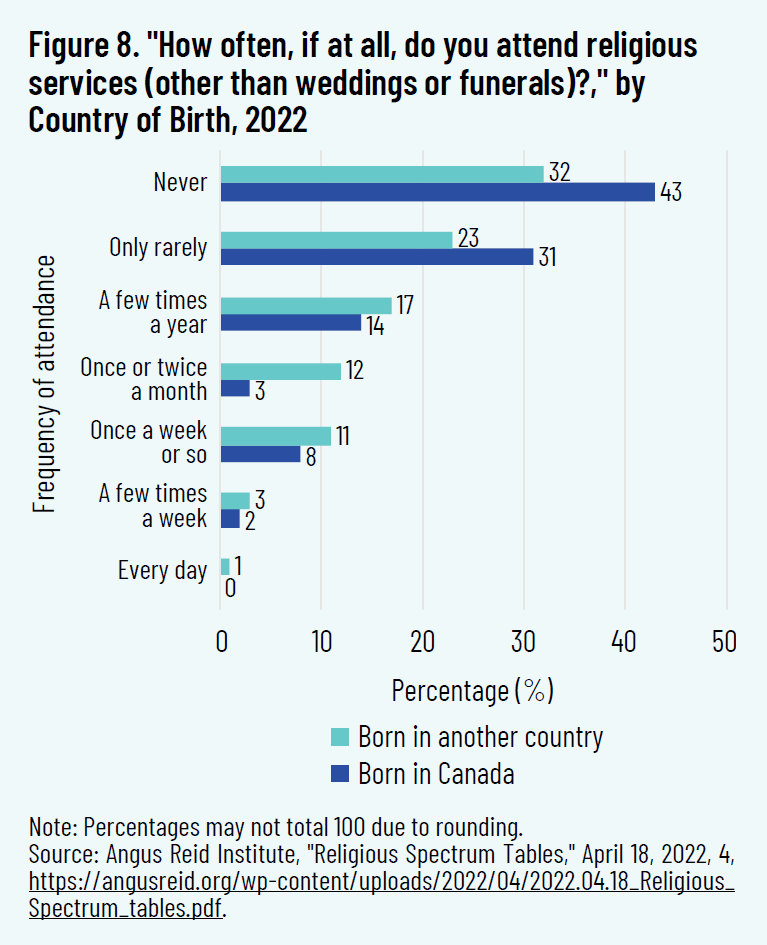

Attending Religious Services

Immigrants also report attending religious services more often than people born in Canada, being twice as likely to attend services (other than weddings or funerals) at least once or twice a month (27 percent, compared to 13 percent). Almost three-quarters of those born in Canada say that they rarely or never attend religious services, while just over half of immigrants say the same (figure 8).

Even though the proportion of Canadians reporting no affiliation with any religion is growing, immigration may continue to offset the overall decline of religious commitment in Canada. Immigration will likely continue to change the composition of religion in Canada as well—more than half of Canadians who report their religious affiliation as Muslim, Hindu, or Sikh were born outside Canada, for example.5

Views on Faith and Public Life

Some Canadians believe that religion is a private matter only—that it belongs in the home and the local congregation, but not in the public square. Those who are committed to their spiritual or religious tradition, however, often believe that their faith is integral to them and cannot be separated from any part of their lives. Further, freedom of conscience and religion is one of the four “fundamental freedoms” enumerated in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.6 Given that immigrants tend to show higher commitment to faith in their everyday lives than the rest of Canada’s population, it is unsurprising that immigrants also tend to see a larger role for faith in Canada’s public life.

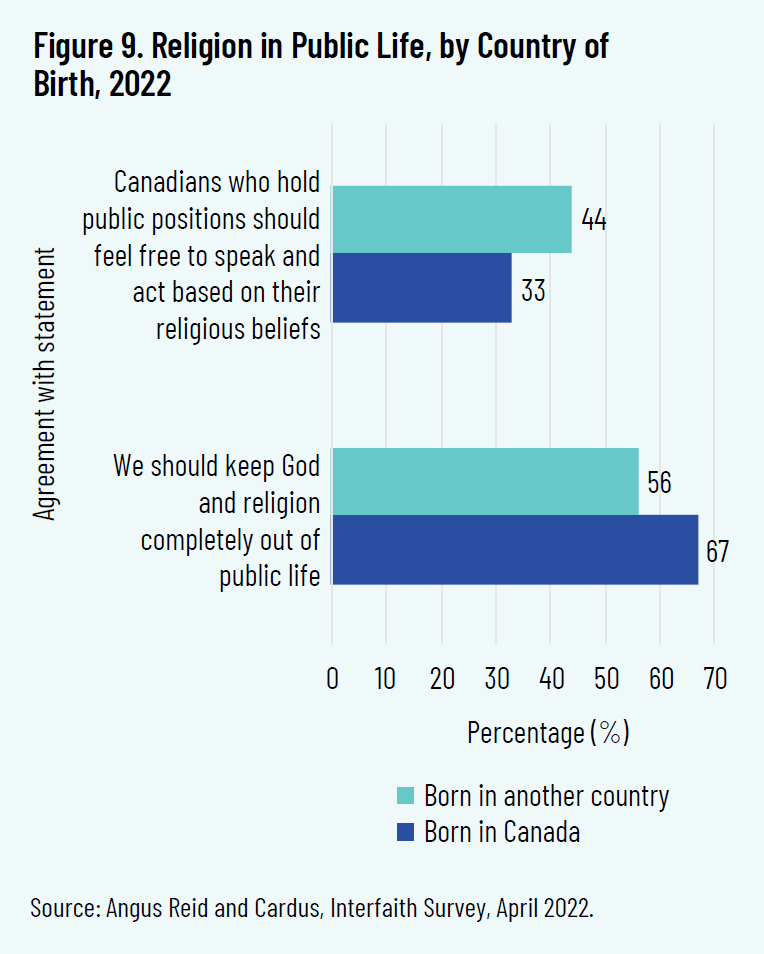

Religion in Public Life

Our 2022 survey asked several questions to gauge respondents’ views about the presence of religion in public life. A majority of Canadians, regardless of their place of birth, prefer to have public life be a space without religion, but the margin is much narrower for immigrants. Close to half of those born in another country say that Canadians who hold public positions should feel free to speak and act based on their religious beliefs, while two-thirds (67 percent) of those born in Canada say that God and religion should be kept completely out of public life (see figure 9).

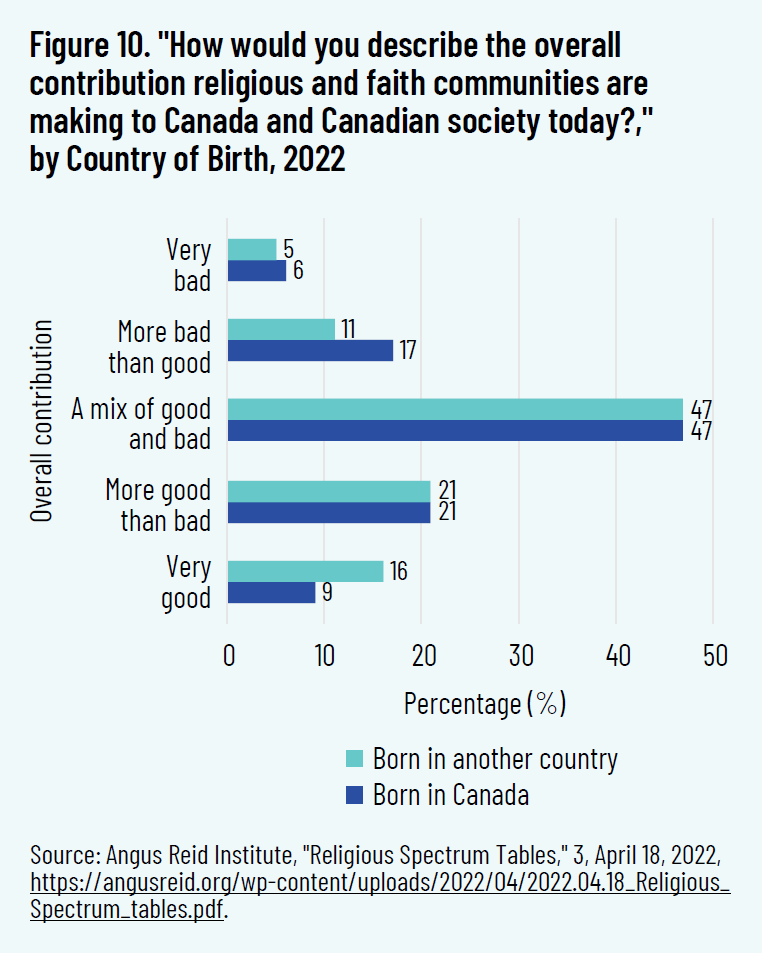

Faith Communities’ Contributions to Society

Immigrants also have a slightly more positive view of the contribution of faith communities to Canadian society. While just under half of those born in Canada and those born in another country say that faith communities’ impact is a mix of good and bad, 37 percent of immigrants say that the impact of these communities is mostly positive, compared to 30 percent of those born in Canada who say the same thing. Meanwhile, 23 percent of those born in Canada say that faith communities’ impact is mostly negative, compared to just 16 percent of immigrants who share the same understanding (figure 10).

Respondents may have had various thoughts in mind as they responded to our survey question, and further research would help to understand these and other responses to our survey. For example, some respondents may have been thinking of one religion in particular; others may have been thinking of religion in general. Some respondents may have brought to mind the individual people they are acquainted with, or their understanding of a faith’s teachings, or the faith viewed as an institution. Similarly, “good” and “bad” can be interpreted in various ways.

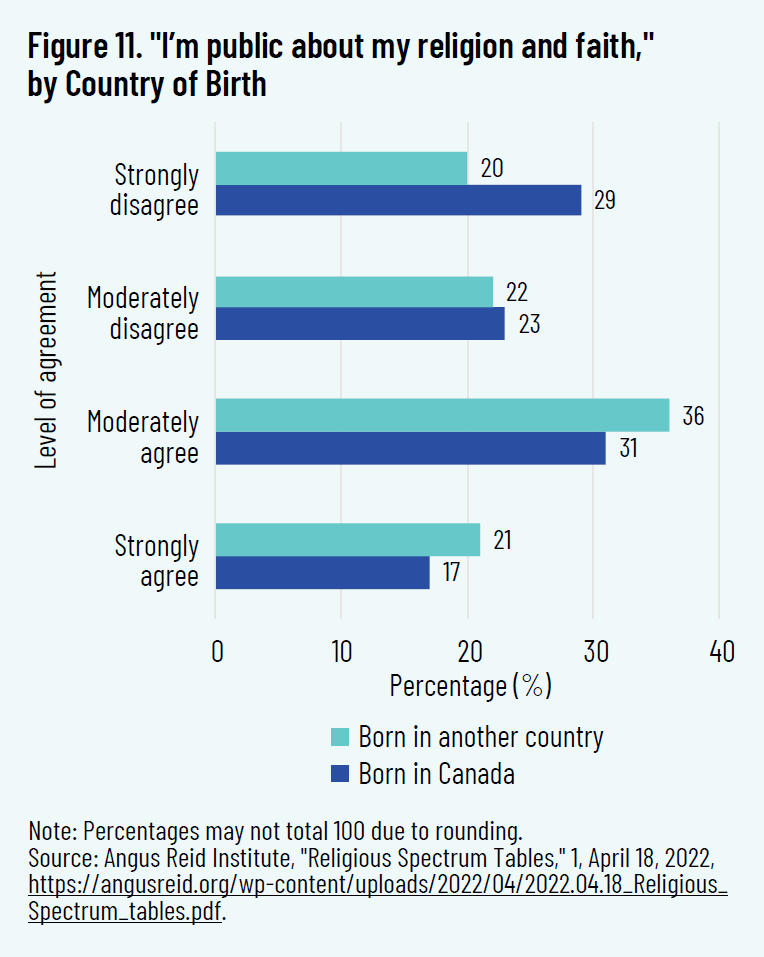

Being Public About Religion

Compared to those who were born in Canada, immigrants are more likely to say that they live out their faith publicly. When presented with the statement “I’m public about my religion and faith,” almost six in ten immigrants (57 percent) said that they agree, compared to just under half of those born in Canada (48 percent) (figure 11).

Respondents may have interpreted this question in various ways. For example, some religious practices involve the wearing of particular clothing, which publicly identifies the person as belonging to that faith. By contrast, some respondents may have interpreted the question as asking about whether they talk about their faith outside of their circle of family and friends.

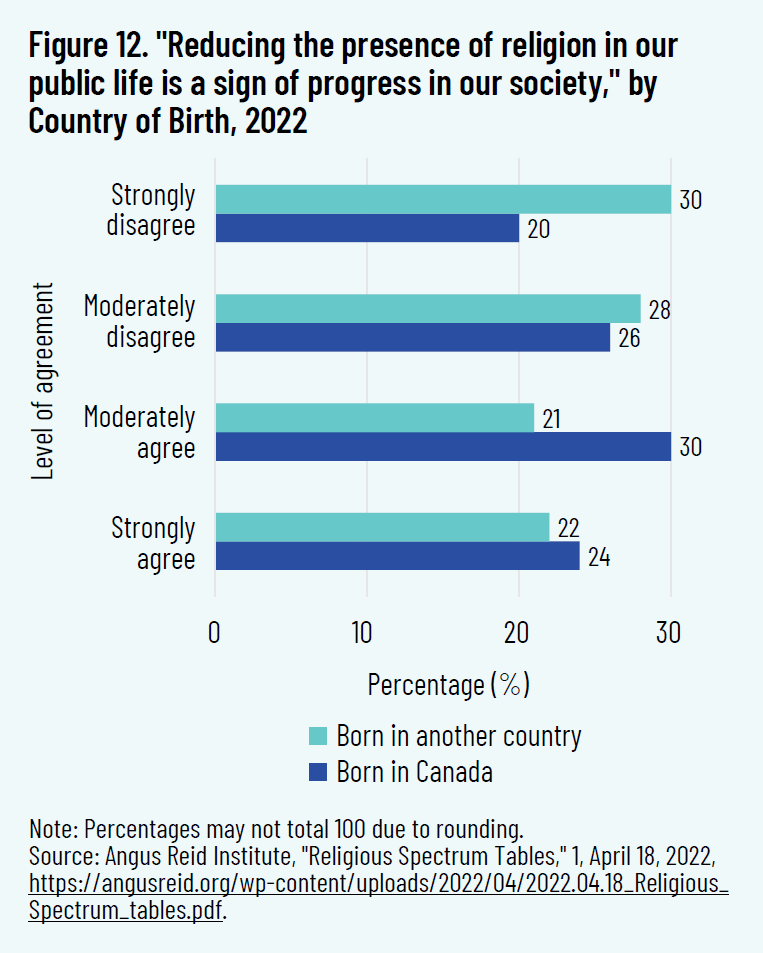

Presence of Religion in Public Life

Those who immigrated to Canada are less likely to say that reducing the presence of religion in public life is a sign of progress in society: 54 percent of those born in Canada agree with this statement, while only 43 percent of immigrants do. Three in ten immigrants strongly disagree, compared to two in ten of their counterparts who were born in Canada (figure 12).

As with other questions in our survey, respondents may have interpreted this question in many different ways. Some, for example, may have thought about “public life” in terms of the activities of public institutions (such as saying a prayer at the beginning of a municipal council meeting). Others may have been thinking in terms of the public activities of individual citizens.

Accommodating Faith Practices and Religious Minorities

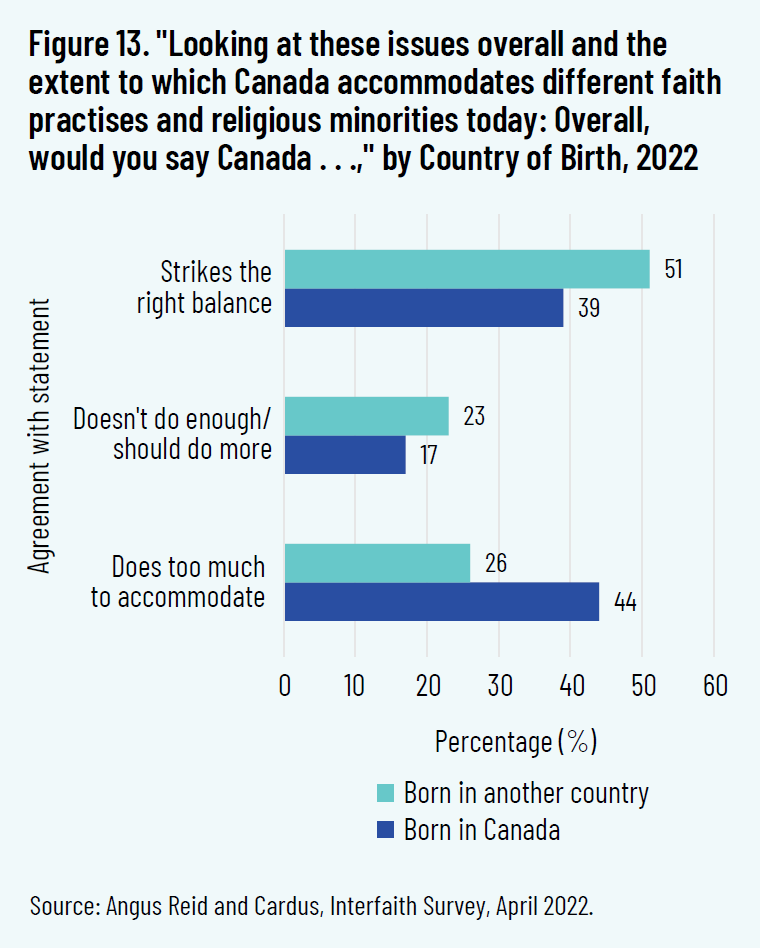

Immigrants are more likely to believe that Canada could do more to accommodate religious minorities. When asked to consider the extent to which Canada accommodates different faith practices and religious minorities today, about half of immigrants say that Canada strikes the right balance, while almost a quarter say that Canada does not do enough. In contrast, only about four in ten of those born in Canada say that the country is striking the right balance, and 44 percent say Canada does too much to accommodate different faiths (figure 13).

Conclusion

Surveys of Canada’s growing immigrant population suggest that, across a variety of measures, immigrants have a higher commitment to religious and spiritual practices than their Canadian-born counterparts. Given these data, it is perhaps not surprising that immigrants also support a larger role for religious expression in public life. As all Canadians seek to keep their country a welcoming home for immigrants, we would do well to consider how we might welcome immigrants’ faith and spirituality as well.

[Source: CARDUS]